When I was thirteen years old, my fellow eighth-grade band member Steve Afendoulis asked me to join a band he was forming. I had been playing the alto saxophone a year, and in that time, thanks to an arcane formula for success called “practicing consistently,” I had ascended to the rank of first chair. Now here was an opportunity to take the music to the next level, and it held the added enticement of lifting me up the social ladder from “weird kid” to “cool kid.” With visions of rock star glory in my head, I accepted Steve’s invitation. I knew it wouldn’t be long before Eric Clapton would be giving me a call. There would be tours, concerts at the Fillmore East . . .

When I was thirteen years old, my fellow eighth-grade band member Steve Afendoulis asked me to join a band he was forming. I had been playing the alto saxophone a year, and in that time, thanks to an arcane formula for success called “practicing consistently,” I had ascended to the rank of first chair. Now here was an opportunity to take the music to the next level, and it held the added enticement of lifting me up the social ladder from “weird kid” to “cool kid.” With visions of rock star glory in my head, I accepted Steve’s invitation. I knew it wouldn’t be long before Eric Clapton would be giving me a call. There would be tours, concerts at the Fillmore East . . .

Steve’s band turned out not to be exactly a horn version of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Its name was the Formal Aires, and “Purple Haze” was not in our library. “In the Mood” was, and so was “One O’Clock Jump,” and “String of Pearls,” and “Mood Indigo,” and lots of other corny old tunes written by corny, passe composers like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Billie Strayhorn, Cole Porter, Carlos Jobim, and Miles Davis. Well, maybe not Miles.

Good-bye, Fillmore East. Visions of beautiful hippie girls falling at my feet dissolved into inebriated granddads twirling their sport coats lasciviously on country club dance floors as my band mates and I honked out “The Stripper.” It was not what I had pictured.

Yet I liked it. And as weeks of practice turned into months, and the months paid off in prestigious gigs, and the band’s library grew along with our sound and our reputation, I came to love it.

The Formal Aires was my introduction to big band jazz, the American songbook, and supercool, genius composers like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Billie Strayhorn, Cole Porter, and Carlos Jobim. Miles Davis was still a little ways down the pike, but regardless, here was a musical foundation on which to build a huge part of my life. It was God’s grace delivered to me on a silver platter, though I was too callow at the time to realize what a remarkable gift I was being given. That’s the nature of grace: the value and the force of it often don’t become apparent to us until long after the fact. All I knew was, I sure was having fun.

Steve’s dad, Gus, managed the band. Gus was wonderful! He doted on us kids, loved our music, and supported us any way he could. As the owner of a tuxedo shop, he saw to it that we were all properly attired for our ongoing calendar of gigs at topnotch country clubs throughout Kent County and elsewhere in Michigan.

And Gus did something else as well, something critical to the success of our fledgling seventeen-piece ensemble: he got Ted Carino to provide musical directorship.

Every week, when we gathered for rehearsal in the Afendoulis basement, there was Ted. An alto saxophonist steeped in the big band tradition, he helped us interpret those stiff black hieroglyphs on our charts into the language of swing, where eighth notes become loose and greasy and feelingful.

Ted raised our appreciation for dynamics. Ted drilled us till the awkward parts fit together into a tight musical gestalt. The concept of “sectionals”—breaking up into sax, trumpet, trombone, and rhythm sections to practice a tune separately—first came to me from Ted Carino.

So too did the impact the right mouthpiece could have on my playing. I had been using the stock mouthpiece that came with my Conn 6M alto. It never occurred to me that there might be other possibilities. Then one night Ted pulled me aside. “Try this,” he said, handing me a little box. In it was a new Brilhart Ebolin mouthpiece. It looked cool with the white bite plate. I put it on my horn and was surprised at how much louder it sounded and how much freer it blew. It was authoritative.

“You need something like this for playing lead,” Ted told me.

Who knew? Certainly not me or my folks. But Ted did, and he spent his cash to give me a mouthpiece that kicked my sound and my playing up a notch to where they needed to be for a section leader.

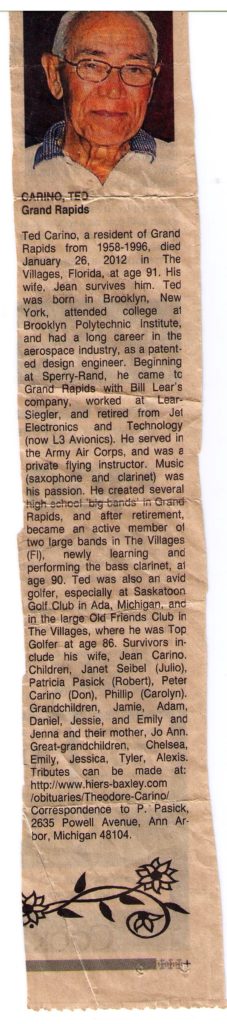

I played with the Formal Aires through my high school years, up to the time when the band disbanded and its members scattered to pursue college, careers, marriage, and raising familes. A few of them remained in music, one of them being me. As for Ted, I eventually lost track of him. He retired from Jet Electronics and moved to Florida, where he remained musically active; you can read about that and lots more in his writeup at the top of this post. I clipped it from the Grand Rapids Press obituaries section in 2012, and having recently rediscovered it, I got to thinking about Theodore Carino and who he was to me.

Ted was a generous man with his time, talent, and knowledge. He invested himself freely and wholeheartedly in a bunch of young players way back when, and today I think there’s not a one of us who wouldn’t remember him with gratitude—given a little prompting, of course. It has, after all, been a few years. But a good person’s impact has staying power, and it can perpetuate itself over time. Ted was one of a few special, key encouragers who made me think, “I can do this. I can play this crazy instrument. And I love doing so.”

I hope there’ll be a few younger souls who, in different ways, can look back forty years from now and say something similar about me—not necessarily about music (though that would be great), but about how I encouraged them to become who they are and affirm the talents God gave them as good and worthy of cultivation. That, even more than the music, would be a great legacy for Ted Carino to have passed on through one young teen to generations still to come.